George Panjara (1938-2017)

ജോർജ്ജ് പാഞ്ഞാറ

George Panjara

Composer and performer of Christian Karnatic classical music in Malayalam "നാദവാദ്യസമേതമായ് നിൻ

നാമഗീതികൾ പാടുവാൻ

ഏകി മാനവ ജൻമമീമുഗ്ദ

ഭൂവിൽ ഗായകനായിമേ”

" With voice and instrumental accompaniment

To sing the praise of your name

You {O Lord} gave me human life on this

Earth as a singer "

Joseph J. Palackal

(Copyright ©2018 Joseph J. Palackal)

George Panjara (1938-2017) was a gift from God to Malayalam-speaking Christians in Kerala, especially the Syro Malabar Catholics who failed to unwrap and appreciate him while he was alive. This is the story of an extremely gifted poet-composer who dedicated his life to celebrate his Christian faith through the performance of Karnatic classical music. Born in a traditional Syriac Christian family, Panjara was inclined, early on, toward South Indian classical music.

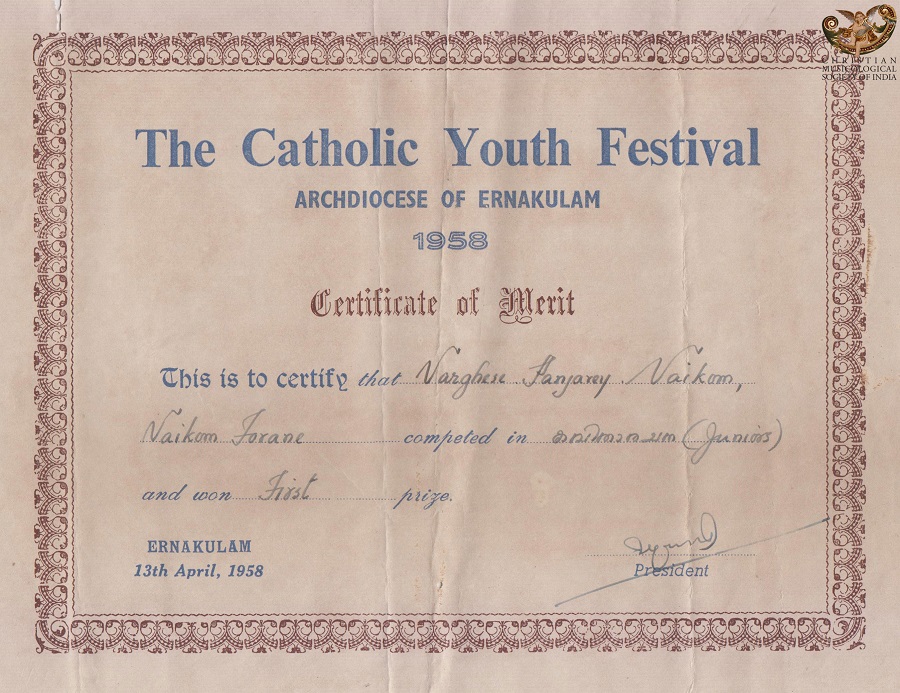

Panjara’s native place, Kothavara, is adjacent to the historic town of Vaikom. The most important institution in this town is the Shree Mahadeva temple which has a significant place in Indian political, social, and cultural histories. The main offering in this temple during the festival season, is music. Famous and aspiring Karnatic classical musicians come here and perform their art as an offering to Lord Shiva, the presiding deity of the temple. Thus, people in the vicinity have the fortune to listen to great performers. Besides, for many years, the temple used to play recordings of classically based Hindu devotional songs through public address system in the early mornings. This is the environment in which Panjara grew up, and his mind and body resonated with the music that was in the air. Panjara decided to learn Karnatic music from Maestro Vaikkom Balakrishnan Nair, who was associated with the Vaikom temple. After mastering the art of classical music, Panjara redirected his life journey as a performing artist. Similar to the great composers in the Bhakti tradition, Panjara composed Christian devotional songs in Malayalam and performed them in a concert format.

George Panjara was gifted with supple vocal cords, a solid, baritone voice with a range that extended beyond two and a half octaves; he also had a brilliant mind that absorbed and processed information, musical or otherwise, that came on his way from varied sources. He educated himself on the nuances of the Malayalam language by reading books. This self-learning gave him courage to venture into various literary genres as poetry, drama, short stories, and novel. By 2009, Panjara had already 300 compositions with Christian themes to his credit. This is an extra ordinary corpus of Christian literature that he has bequeathed to Kerala and Christianity. He also had a vivid imagination creating visual images through word painting.

2. Releases of George Panjara

Alphabetical list of compositions by Panjara

From the 300 or more compositions, we have been able to collect only 68 lyrics. There are audio versions of 34 compositions in the five commercial releases. We were fortunate to obtain the audio tracks of the first commercial release in 1985 by Chavara Cultural Center, Ernakulam. In the list of 68 compositions we see Panjara used 52 ragam-s; some of these are rare ragam-s. It is truly amazing to see that within six years of training in Karnatic classical music, Panjara mastered a remarkable amount of ragam-s. Only a person with an extremely brilliant mind could have done that. In the song titles in the list we also see the wide range of topics and an indication of the extraordinary mastery of the Malayalam language.

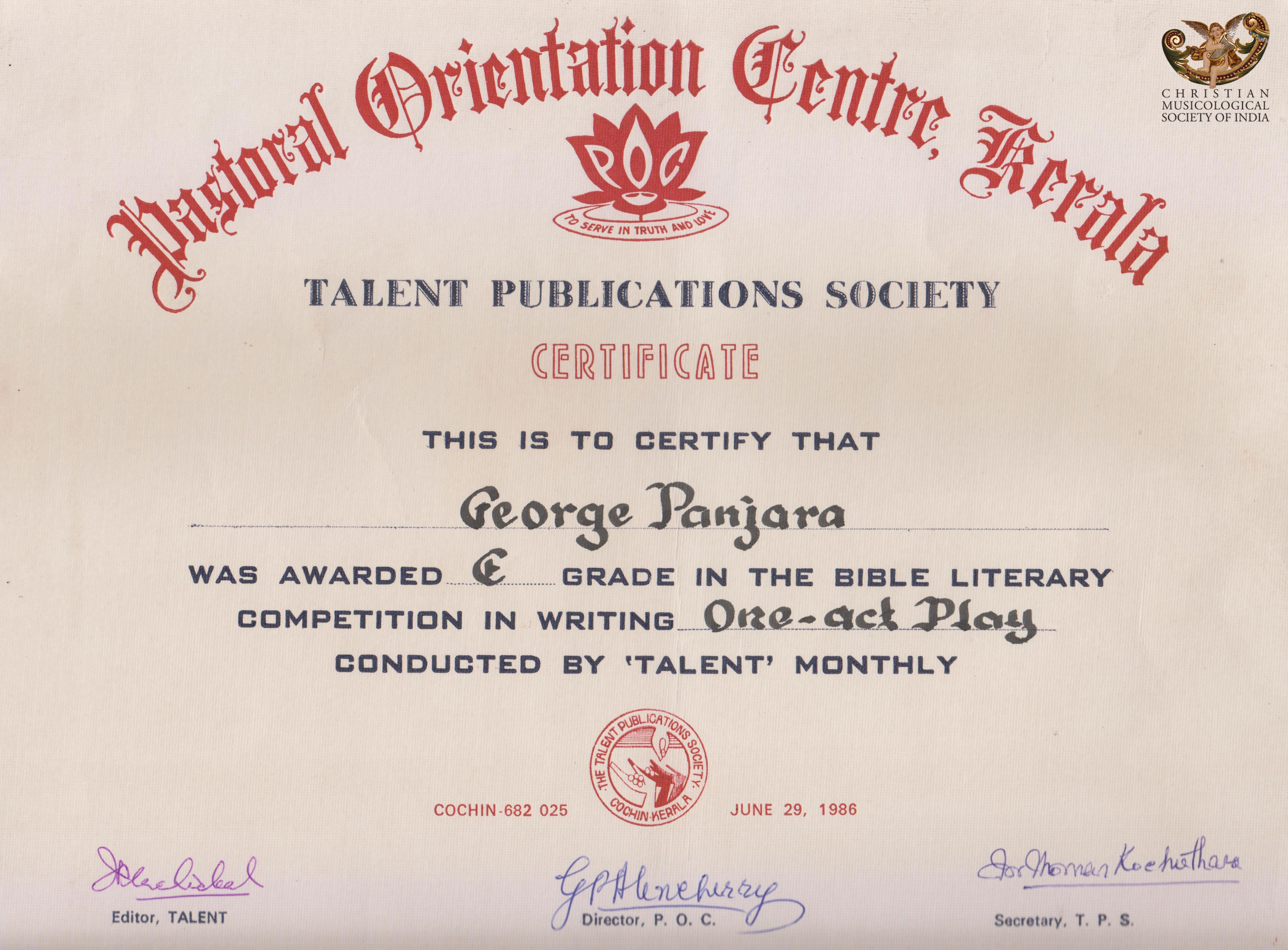

Before emerging as a composer of classical music, Panjara started as a poet. Later, he moved on to such other genres as drama, short stories, and novel. Some of those works found space in Catholic publications. These works, too, show an impressive command of the Malayalam language.

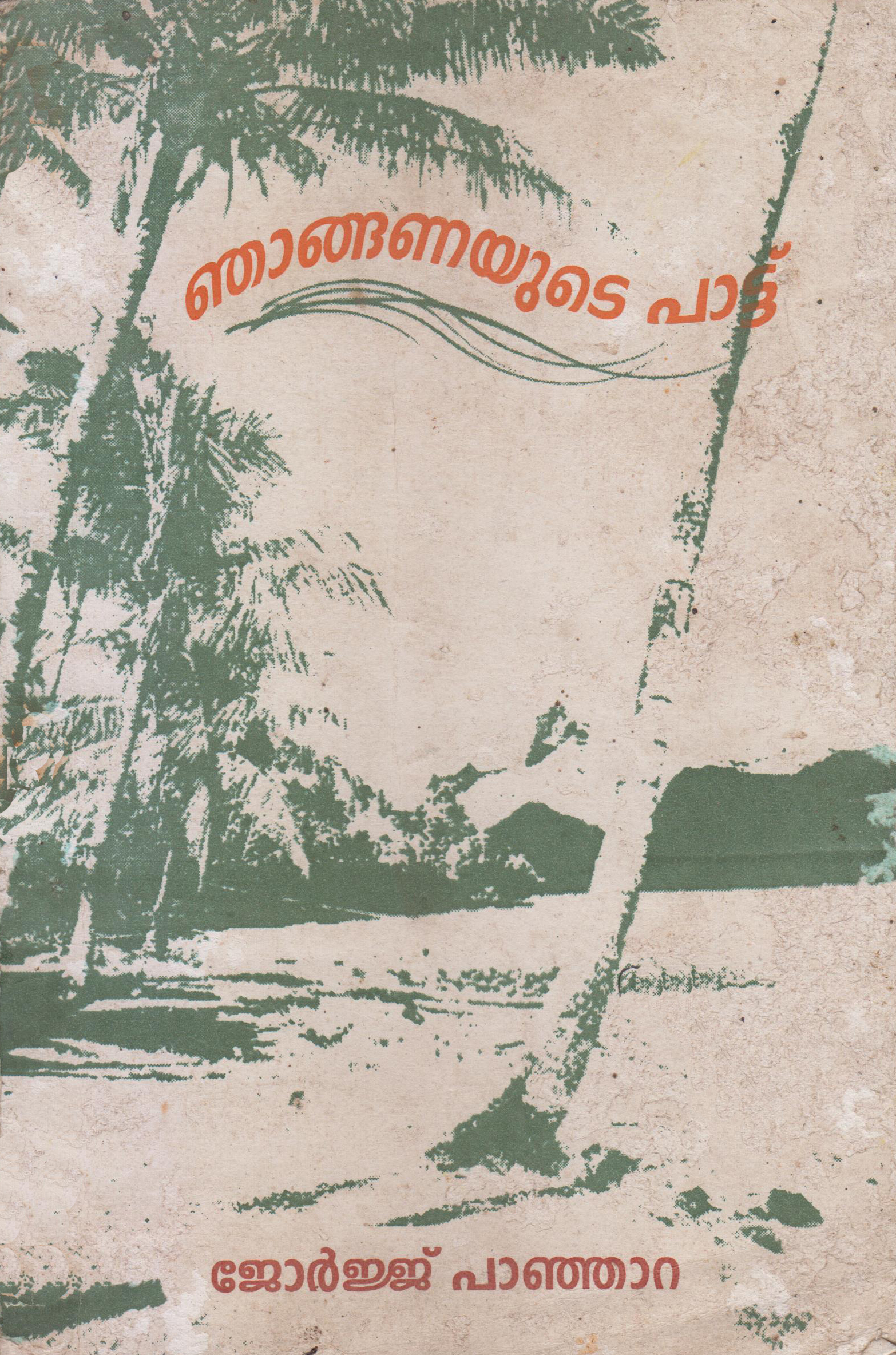

Fr. Joseph Thachil’s preface to the collection of Panjara poems, ഞാങ്ങണയുടെ പാട്ട് n͂āṇkaṇayuṭe paṭṭǔ “song of the reed”, published in 2002 , is an excellent tribute to Panjara’s exceptional poetic skills. Fr. Thachil’s stylistic Malayalam text defies easy translation; therefore, a scanned copy of the original pages are attached here for the benefit of curious readers pdf dowload

The Bible is the primary source of inspiration for Panjara’s faith-filled literary works. One can only be amazed at the level Panjara internalized the biblical stories. Those stories, however, take an all too different life in the vivid imagination of Panjara. Rhyme and rhythm in the verses add silent musicality in the mind of the reader.

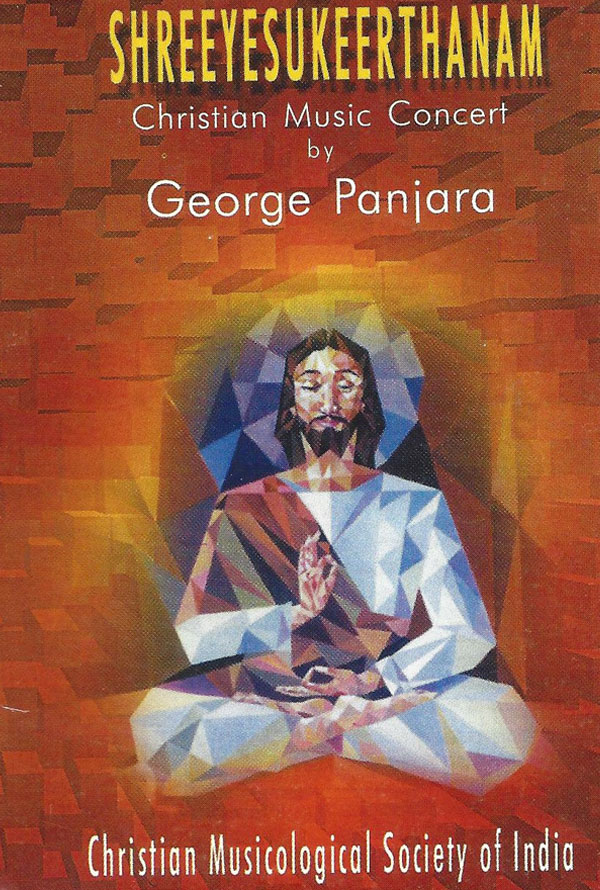

Panjara’s lyrics are also embedded in personal experiences. For example, let us examine track 4 in Sreeyesukeerthanam that the Christian Musicological Society of India produced:

| പരിഹാസരാജാവായ് പരിതാപമേറ്റുവാങ്ങി | Parihāsarājāwāy – Parithāpamēttuwāngi |

| പരിദീനദയാമയാ യേശുനാഥാ നീ | Paradīnadayamaya yēshunadhā nī |

| പരമോന്നതാ സുതാ - നരവംശപൂജിതാ | Paramonnathā suthā – naravamshapūjithā |

| ദുരിത നിവാരണാ – പരമകൃപാനിധേ | Durithaniwāraṇā - paramakṛipānidhē |

| ശിരസിൽ കിരീടമായി - മുൾമുടിചൂടി കയ്യിൽ | Ṥirassil kirīdamāyi – muḷmudichūdi kaiyyil |

| രാജാധികാരച്ചെങ്കോ - ലായൊരുഞാങ്കണയും | Rajādhikārachenkō – lāyorunjāngaṇayum |

| പരലോക കവാടത്തിൽ - ഞാനണഞ്ഞീടുംനാളിൽ | Paraloka Kawādatthil – njānanajīdumnāḷil |

| പരിഹാസമേറ്റിടായ് വാൻ നീ തുണയേകണമേ | Parihāsamēttidāywān Nī thuṇayēkaṇamē |

The opening verses take us to the scene of Jesus’s trial at the court of Pontius Pilate, where, after Pilate sentenced Jesus to death on a cross, the soldiers took Jesus to their quarters and ridiculed Him. There are a few biographical elements in these lyrics; probably, only very few people would know about them. Early in his musical career, Panjara had a habit of visiting church leaders and voluntarily singing before them. One day, he visited a prominent priest in the Syro Malabar Church who was the director of a reputed institution. As usual, Panjara sat before him and started singing one of his compositions. When he finished, the priest was annoyed and said, “edō, ārkkuvēṇam thante e sangītam?” എടൊ ആർക്ക് വേണം തന്റെ ഈ സംഗിതം ? (Hey man, who wants your {this kind} of music?). Obviously, the priest did not like Karnatic classical music, and in his opinion, such music would not appeal to Christians even though the lyrics were Christian. It was a blatant ridicule; the priest did not conceal his displeasure of Panjara wasting his time. What caused him pain was the way the priest addressed him, “edō,” which is not a very respectful way of addressing someone, even a person on lower level of social hierarchy.

The second experience happened at St. Antony’s Monastery at Aluva sometime in 1988. The monastery used to organize annual Bible convention at the open air stadium on the monastery grounds. About a thousand people attended the three-day convention. The organizers accepted my suggestion to have a Christian classical music concert by Mr. Panjara and his team on the last day of the convention. Unfortunately, the concert did not appeal to the audience. Twenty minutes into the concert, the audience began to walk out of the stadium, one by one. Only a handful of people stayed until the end. Obviously, the priests were annoyed at scheduling an unpopular program on such a special occasion. It is possible that these two experiences influenced this composition. That being said, the lyrics take an introspective turn at the last two verses:

|

പരലോക കവാടത്തിൽ ഞാനണഞ്ഞീടുംനാളിൽ പരിഹാസമേറ്റിടായ് വാൻ നീ തുണയേകണമേ |

Parlōka kawāṭatttil jnanaṇanjīṭumnāḷil Parihāsmētʹt ʹiṭāywān Nī tuṇayēkaṇamē |

Here Panjara places himself at the scene of the last judgment Mt 25: 31-46; he prays that he may not be kept on the left side of the King to hear the words of ridicule and final damnation. The application of the biblical images and the evolution of ideas through the verses show Panjara’s extraordinary poetic caliber and an in-depth understanding of the Bible.

The opening verses from track 5 from the Nadopasana release is yet another example of Panjara’s literary craft.

| ഗീതദിവ്യകലാനിധേ സം - | Gītadivyakalānidhē - sam |

| മോദരൂപ ദയാനിധേ – സം (ഗീത) | Mōda rūpadayānidhē - sam |

| നാദവാദ്യ സമേതമായ് നിൻ | Nādavādya samēthamāy nin |

| നാമഗീതികൾ പാടുവാൻ.. | Nāmagīthikaḷ pāduwān |

| ഏകി മാനവ ജന്മമീ മുഗ്ദ്ധ | Ēki mānawa janmamī mugda |

| ഭൂവിൽ ഗായകനായിമേ- സം (ഗീത) | Bhūwil gāyakanāyimē - sam |

| മധുവചനാമൃത ലോലുപാ നിൻ | Madhuwachanāmṛitha lōlupā nin |

| മധുര കഥാസുധ നുകരുവാൻ.. | Madhura kathāsudha nukaruwān |

| ജാത കൗതുകമീജനം കാ- | Jātha kouthukamījanam kā |

| തോർത്തിടുന്നു മഹീപതേ.. | Thōrthidunnu Mahīpathē |

| നാദസൗഭഗമായി നീയെൻ | Nāda soubagamāyi nīyen |

| നാവിൽ വാ യേശുനായകാ - സം (ഗീത) | Nāwil wā yēśunāyakā - sam |

Here the suffix “sam” at the end of the first verse becomes a prefix to the first word at the fourth iteration of the verse, and then it becomes a prefix to the first word in the second verse. This is an interesting semantic and syntactic display which requires an excellent command of the Malayalam language.

In track 6 in the Nadopasana release, Panjara’s poetic imagination takes flight during his conversation with the tender breeze on the valley of the Bethlehem hills, on the Christmas night.

| ബദ് ലഹേം കുന്നിന്റെ താഴ് വരിയിൽ നീ | Bethlahēm kunninte thāz warayil nī |

| പോകുമോ പോകുമോ കുളിർകാറ്റേ | Pokumo pokumo kuḷṛkkāttē |

| മുല്ല പൂമണം കയ്യിൽ കരുതിയോ നീ ? | mulla Pūmanam kayyil karuthiyō nī |

| ആ ചെറുഗുഹയിൽ പള്ളിയുറങ്ങുന്ന | Ā cheṛuguhayil paḷliyurangunna |

| തീശ്വരപുത്രനാണേ - കാറ്റേ | Thīśwaraputhṛanāṇē – kattē |

| എന്നുണ്ണിയേശുവാണേ | Ennuṇṇiyēśuwāṇē |

| വേഗം കടന്നു നീ ചെല്ലരുതേ, പിഞ്ചു | Wēgam kadannu nī chellaruthē, pinchu |

| മേനി കുളിർന്നു വിറച്ചു പോകും | Mēni kulirnnu viracchu pōkum |

| പൂമണം കാൽക്കൽ നീ കാഴ്ചവെച്ചാൽ മന്ദം | Pūmanam kālkkal nī kāzhchawechāl mandam |

| പോരണം രാത്രിയാണേ- കാറ്റേ | Pōraṇam rāthṛiyāṇē – kāttē |

| മഞ്ഞുള്ള കാലമാണേ... ബദ് ലഹേം | Manjulla kālamāṇē . Bethlahēm |

He invites the breeze to join him to the cave of nativity, and instructs the wind to be very gentle and careful while entering the cave in view of the fragility of the new born infant

All the above examples show Panjara’s uncanny skill to use poetry as painting. Yet another example of word painting is track 2 in the CMSIndia release, in which Panjara describes the scene of Jesus approaching the disciples by walking on the water Mt 14: 22-33.

| സാഗരസലിലോപരി പാദചാരിയായി നീ | Sāgarasalilōpari pādachāriyāyinī |

| യേശുവേഗമിച്ചുവോ തോഴരൊത്തുചേരുവാൻ | Yēśuwēgamicchuvō thōzharothuchēruwān |

| ആഗതൻ നിൻ ദർശനം ഭൂതമെന്ന ശങ്കയാൽ | Āgathan nin darshanam bhūthamenna shangayāl |

| ദേവദേവ നിൻ സ്വരം കാതിൽ വീണമാത്രയിൽ | Dēwa dēwa nin swaram kāthil wīṇamāthrayil |

| ലോകജീവിതാർണ്ണവം താണ്ടിടുന്നു ഞങ്ങളും | Lōkajīwithārnnawam thāndidunnu njangalum |

| ലോകനായകാ കരം നൽകി നീ തുണയ്ക്കണേ | Lōkanāyakā karam nalki nī thuṇaykkanē |

| ആ വിശുദ്ധമാനവർ മോദമാർന്നു സംസ്മിതം | Ā wishudhamānawar mōdamāṛnnu samsmitham |

| ഭീതരായ് വിബോധരായ് സാധുതോഴരാകെയും | Bītharāy vibōtharāy sādhuthōzharākeyum |

Panjara’s compositions are an exercise in biblical meditation. One can only be amazed at his understanding of the Bible. In performance, Panjara takes us to yet another deeper level of meditation during the “niraval” section, where in the performer takes a single phrase or line and improvises on it by elaborating the different shades of meaning of the same phrase, while staying within the parameters of the ragam.

Panjara’s overflowing devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary deserves a special mention. In every concert, he would sing at least one composition on the Blessed Virgin. Among the 68 compositions in the list above, twenty are on the Blessed Virgin. Among the Marian hymns we see an interesting compositional gesture; sometimes, Panjara selects the ragam whose name matches with the opening words of the lyrics.

| CMSI No. | Title | Ragam |

| 09-264 | Naḷinakusumōpamē നളിന കുസുമോപമേ | Naḷinkānthi നളിനകാന്തി |

| 09-285 | Naḷinakānthišṛī നളിനകാന്തിശ്രീ | Naḷinkānthi നളിനകാന്തി |

| 09-293 | Pūṛnachandrikāsamāna പൂർണ്ണ ചന്ദ്രികാസമാന | Pūṛnachandrika പൂർണ്ണ ചന്ദ്രിക |

| 09-297 | Laḷithēdēwamāthē ലളിതേദേവമാതേ |

Laḷitha ലളിത |

| 09-272 | Wasanthasumasundari വാസന്തസുമസുന്ദരി | Wasantham വസന്തം |

| 09-263 | Šṛīranjini ശ്രീരഞ്ജിനി |

Šṛīranjini ശ്രീരഞ്ജിനി |

Panjara was the happiest on the concert stage, because concerts gave him the opportunity to set free the texts and melodies that were dancing in his brain. He had an extremely pleasant demeanor and a broad smile on the concert platform. It was evident that he was singing the meaning of the text, rather than the text itself. There were rare instances when music connoisseurs commented negatively on Panjara’s execution of talam. Informed listeners can make their own judgment by listening to the many studio recordings that are posted on YouTube as part of this project. In any case, such comments on his metric sense should not diminish the value of the Panjara compositions.

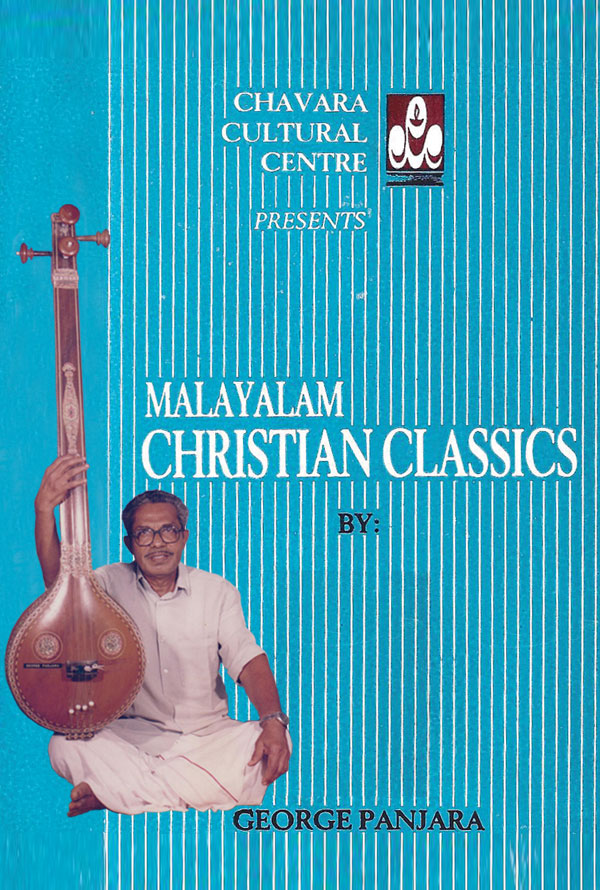

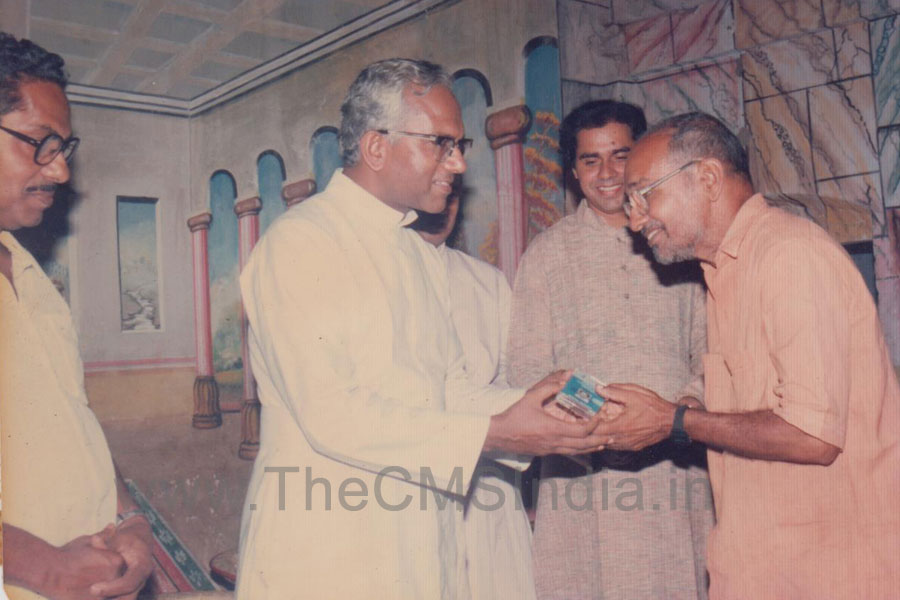

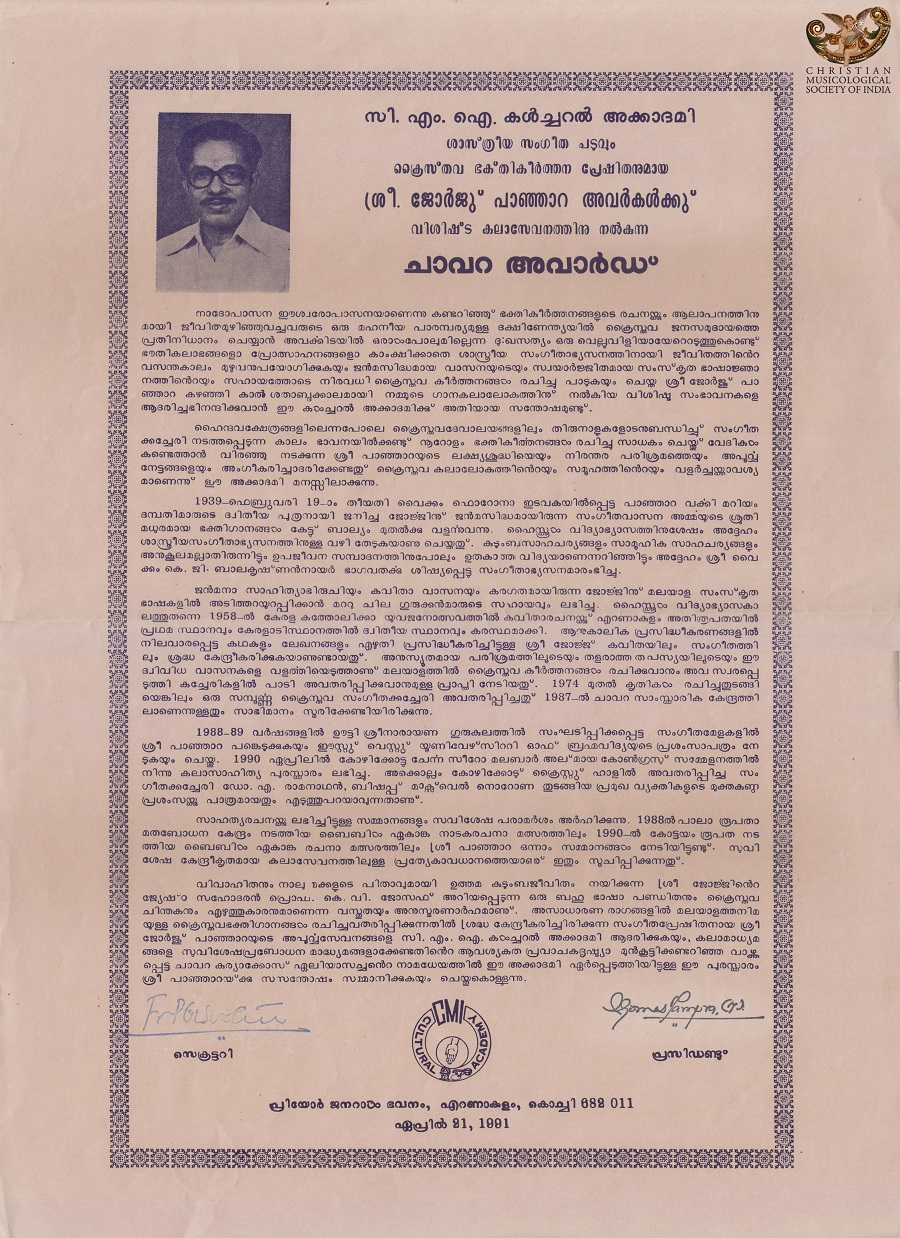

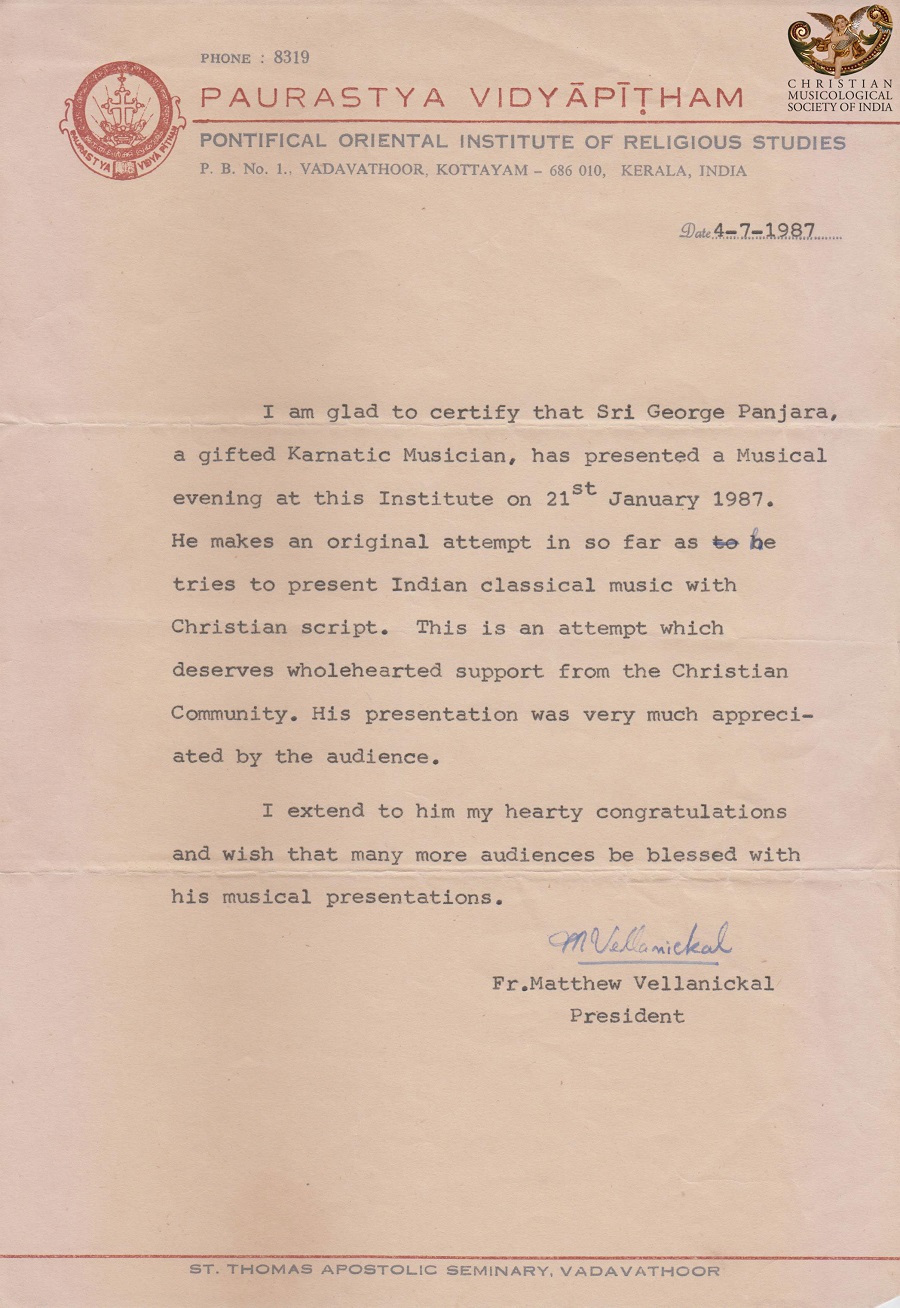

Chavara Cultural Center and George Panjara

In (1985), Panjara introduced himself to Fr. Joseph Ampatt, who was the director of the Chavara Cultural Center at Ernakulam, a CMI institution. Fr. Ampatt was impressed by Panjara’s demonstration of his talent and organized a debut concert at the Center. That happened to be the official launching of his concert career. Later, Fr. Ampatt also released a pre-recorded cassette of selected compositions. This was the first commercial release of Panjara’s compositions. Fr. Joseph Ampatt deserves our gratitude for his avantgarde project to release a pre-recorded cassette of Christian Karnatic classical music, probably the first of its kind in Malayalam. Fr. Ampatt knew that such a project would not be commercially viable; yet, it became a precedence for several other releases in the later years by Nadopasana, Thodupuzha, Christian Musicological Society of India, and Cochin Arts & Communications CAC. The directors of Chavara Cultural Center , who succeeded Fr. Joseph Ampatt, kept track of the contributions of Panjara in the following years. Because of their efforts, the CMI Cultural Academy honored Panjara with a Chavara Award on April 21, 1991.

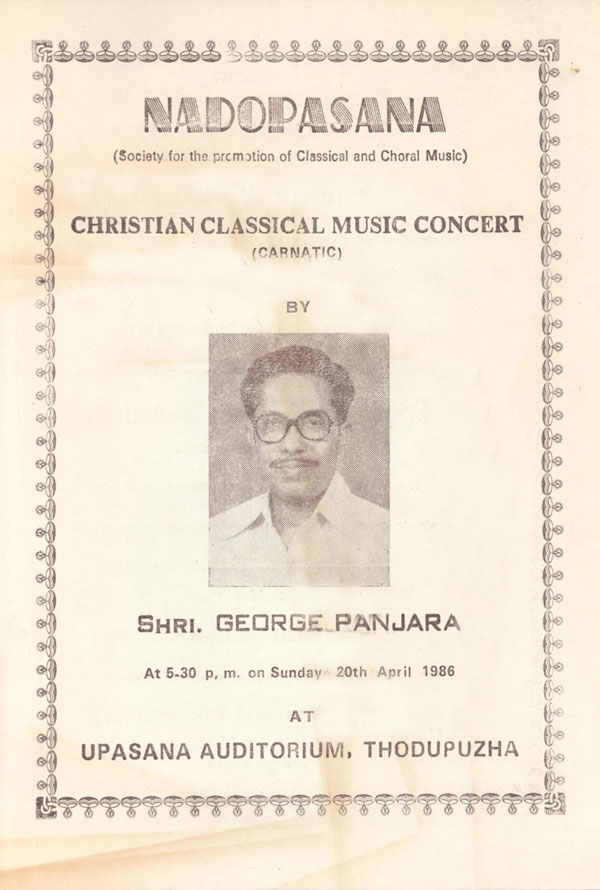

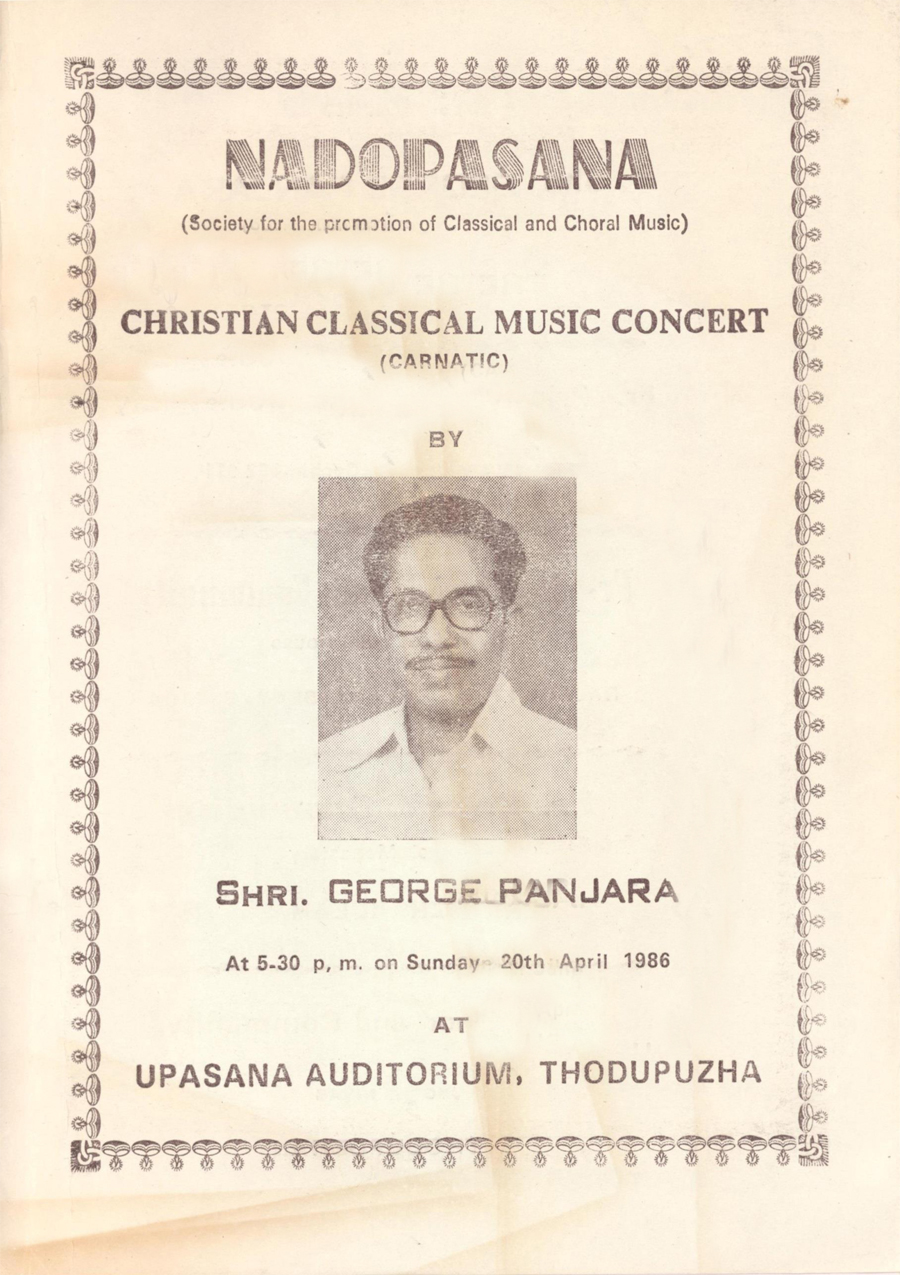

Nadopasana, Thodupuzha and George Panjara

In 1986, when we envisioned Nadopasana, at Thodupuzha, as a Society for the promotion of classical and choral music, Christian classical music was an essential component. Naturally, Panjara became a significant partner in this project. We organized a concert by Panjara on April 20, 1986 We also tried to use the occasion to educate the audience on the Karnatic classical music in general, and on the special features of Panjara’s compositions. Sadly, in the ensuing years under new directors, the Christian classical element did not get much traction. That being said, both directors, Fr. Antony Urulianickal, CMI and Fr. Kurian PuthenPurackal, CMI continued the connection with Panjara. During the terminal, bed ridden years of Panjara, both priests along with Sunny Vempilly visited Panjara at home and payed their respects. In 1988, we also released a pre-recorded cassette of Panjara’s concert, under the banner of Nadopasana. All in all, it is fair to say that the CMI priests and the cultural institutions run by them were the most discerning of Panjara and his unique contributions, with four exceptions.

1. Guru Nitya Chaitanya Yati (1923-1999), a great Keralite, was also a connoisseur of Karnatic music. Every year, Guru Yati would hold a music festival at the Gurukula Ashram in the scenic Ooty hills. One year I performed Christian bhajans at this festival. The Guru heard my singing at an interreligious conference that Fr. Albert Nambiaparampil organized in Ooty and invited me to sing at the festival at the Gurukulam. I gladly accepted the invitation. After my performance, Guru Yati and I spent almost an hour in conversation during which Guru Yati spoke to me about a certain George Panjara with great admiration. Panjara had performed at the Ashram during the previous festival. The Guru, although a Hindu, was immensely glad to listen to Karnatic classical compositions with Christian themes. I was thrilled and felt proud about of fact that Panjara was capable of making such a deep impression on such a great man

{module 392}

2. Fr. William Nellikkal, who currently is in charge of the Malayalam section of the Vatican Radio, is one of the very few priests from Kerala, who understood the greatness of Panjara and the uniqueness of his contribution, and promoted him whole heartedly. While he was director of the Cochin Arts and Communications CAC, an esteemed cultural institution at Ernakualm, Fr. William organized seven concerts by Panjara, and produced two pre-recorded cassettes of Panjara compositions, respectively in (2006) and (2008). It was a great way of honoring Panjara. This is how Fr. William responded to my email query 10 December 2017 on his recollection on Panjara. Fr. William’s candid response throws light on several aspects of the Christian cultural sensitivity or lack thereof among Christians in Kerala.

“Those two CDs of Vidwan Panjara were done in (2006) and in (2008). I had also the joy of arranging at least 7 concerts of Panjara in different places, including one at POC. He was a good composer, more than a performer. His lyrics are also strong, with Sanskrit touch and depth for a classical composition. Panjara's diction was excellent and his voice, far young and clear for his age. Over and above, he was a good and honest Catholic. He was humble and gentle. He was not greedy for money, he spent practically all his talent, hoping to promote Christian classical music, vying with the Hindu culture of Vaikkom. Hoping against hope... he was not recognized by the church. It is true with many Christian classical singers of India, and particularly of Kerala. See such examples as Yesudas, Regi George, Job kuruvila, Jaison Nair, Kumbalam Baburaj stephen and others. Some of them are even turning to Hinduism to eke out a living.Our ancient Christianity in Kerala has not grown enough to appreciate the indigenous music, art or architecture. Except a handful of people like you, Fr. Palackal, and Fr. Poovanthingal, etc. Kudos to Chavaryachan! Though Vatican II gave freedom to adapt ourselves to the indigenous culture, we do not want it!

Ps. to be honest, with regard to Panjara’s singing, occasionally on the stage he missed the thaalavattom, not always... occasionally. May be due to the irregularity and infrequency of performances with pakkamelam.”

3. Goodness TV, a popular Catholic Television channel in Kerala televised a documentary on George Panjara in (2009). This was Panjara’s first exposure on this medium. The program beautifully highlighted the environment in which Panjara lived. It also included Panjara’s own words and comments on his life and music. The audio tracks were not satisfactory; by the time of recording, Panjara’s vocal chords were on the decline. In any case, the program was indeed an honor for Panjara.

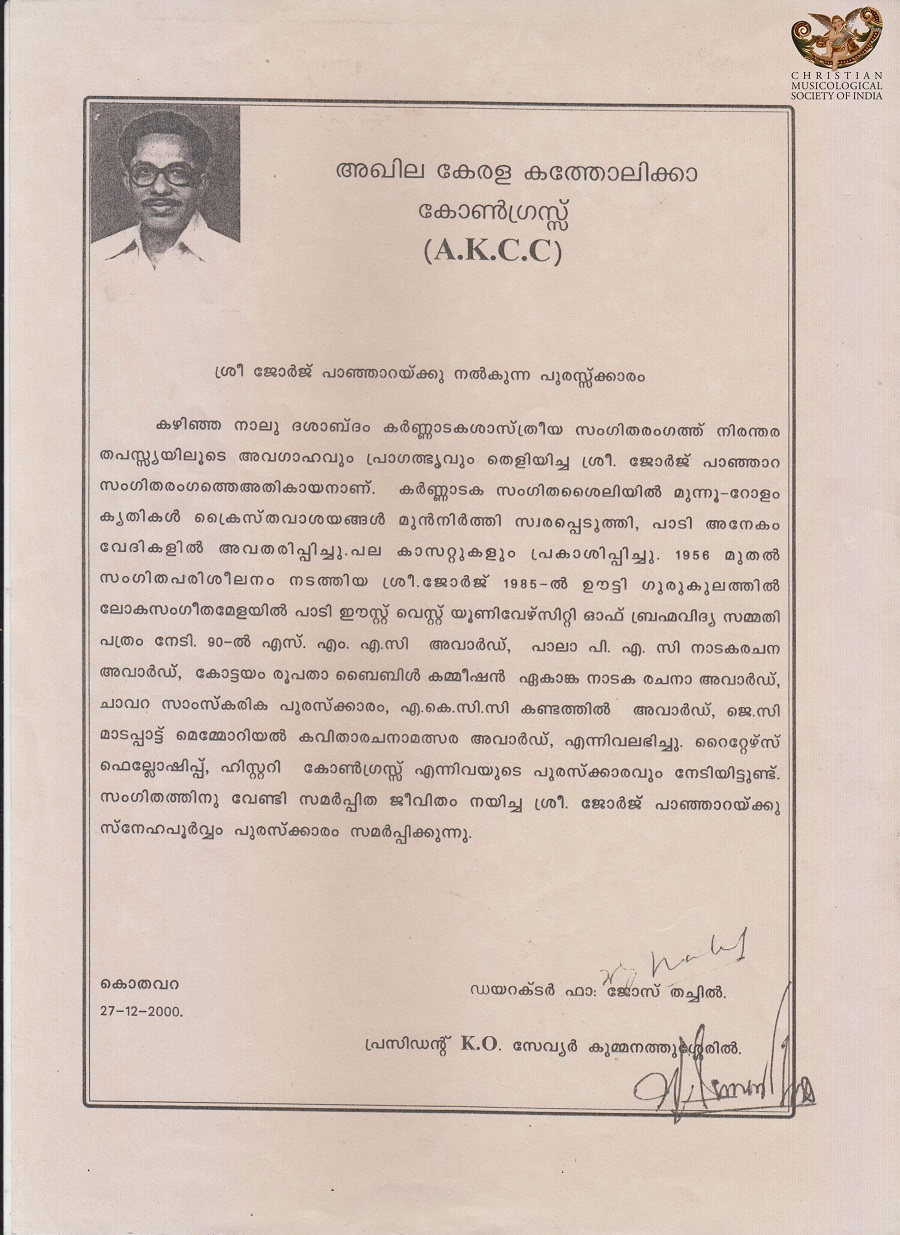

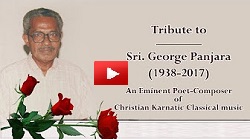

A.K.C.C. and K. C. B. C. Awards

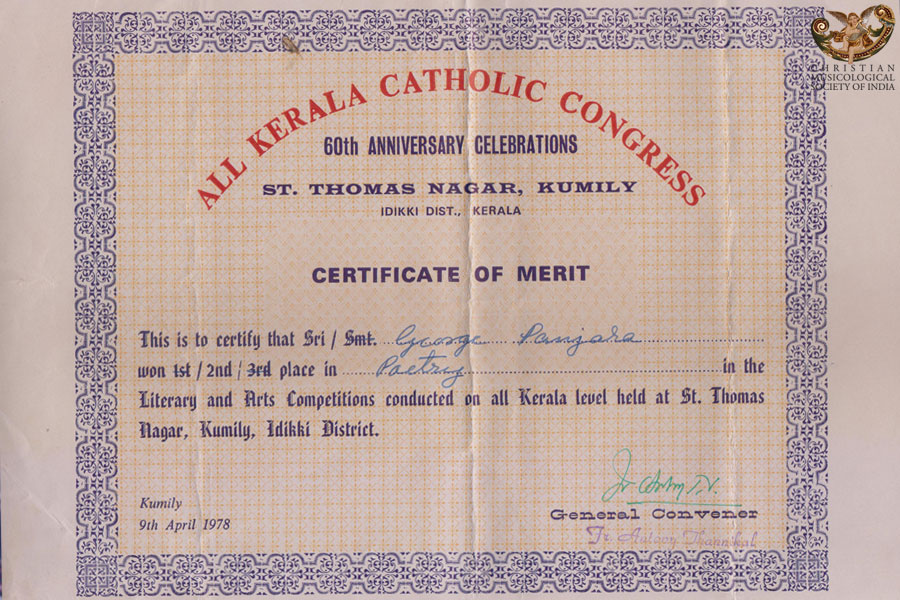

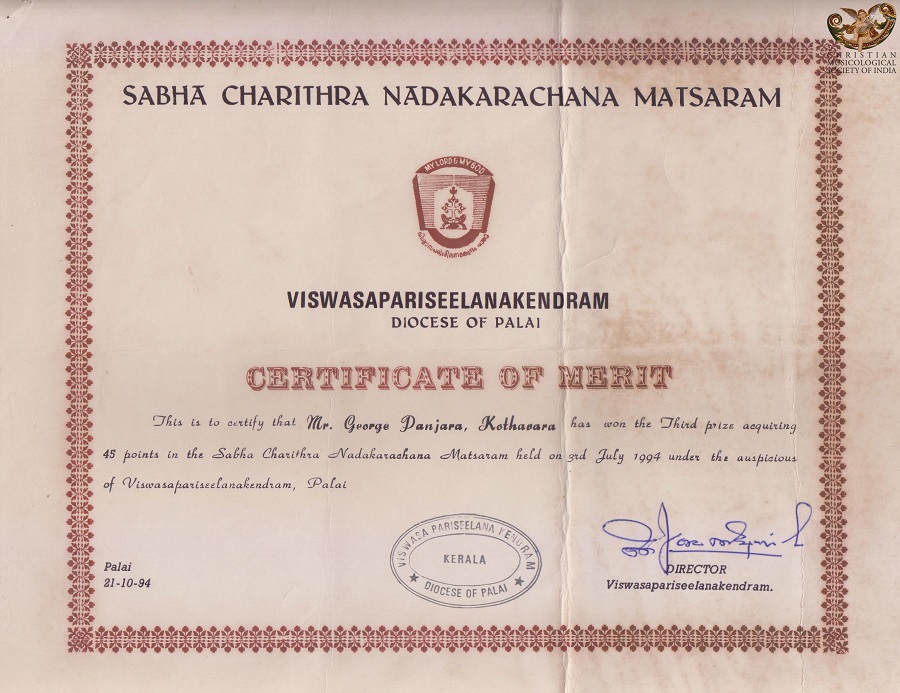

{module 395}4. The All Kerala Catholic Congress acknowledged George Panjara’s contributions and gave him an award, in 2000. Eight years later, the Media Commission of the Kerala Catholic Bishop’s Conference conferred on him the Gurupuja award in 2008. Both awards, one from a Catholic laity organization and the other from the Bishop’s Conference, were high recognitions for George Panjara. Yet, George Panjara’s art did not reach the popular imagination of Kerala Catholics, nor did they translate into more invitations for live concerts.

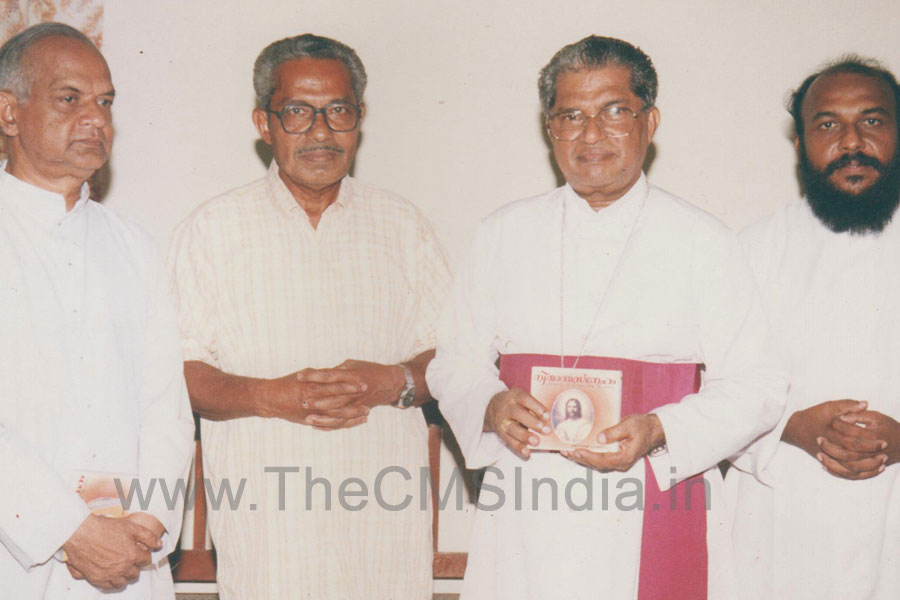

Since its inception, George Panjara was a close collaborator with the Christian Musicological Society of India. The highlight of the first annual meeting (2000) of the Society was Panjara’s Christian classical music concert. The meeting was held at Acharya Palackal Jeevass Kendram, on the campus of the St. Antony’s Monastery CMI at Aluva. We also released a pre-recorded cassette of selected compositions of Panjara on that occasion. As is evident from the photo taken on the occasion, Panjara was immensely happy.

After the annual meeting, we decided to spread the mission of Panjara by organizing an all Kerala competition for Christian classical music. We sought the collaboration of the Media Commission of the Kerala Catholic Bishop’s Conference K.C.B.C.. Our close friend Fr. William Nellikkal, who was the secretary to the Commission at that time, along with Dr. Cherian Kunianthodath, CMI and Sr. Dr. Sheila Kannath, CMC took initiative to organize the event at the Pastoral Orientation Centre at Palariviattom, in Ernakulam. The Society used its own funds for the cash prices for the winners of the competition. We continued this as an annual event for about five years. All this while, Panjara was eager to suggest to add this item in the all Kerala Bible Kalolsawam to get a wider reach of the concept. When Bible Kalolsawam added Christian classical music competition to its agenda, CMSIndia discontinued its competition. Panjara diligently attended the event every year, and was immensely joyous when some of the competitors chose to sing his compositions.

{module 397}

The life story of George Panjara is incomplete without a mention of Nedumangad Sivanandan, a virtuosic violinist in the Karnatic classical tradition, who became a faithful friend and a concert collaborator with Panjara. Sivanandan Master, as was affectionately called, was not only a master of the Karnatic classical music, but also a master of radiant modesty. It was indeed an honor for Panjara to have the celebrated maestro as his accompanist. The maestro also accompanied in many of the studio recordings of Panjara concerts. It was during the rāgawistāram improvisatory exposition of the ragam that one could hear the superior knowledge and artistry of the Master of sensitivity and immaculate intensity. Sivanandan Master had better name recognition among the concert goers; yet, with his restrained virtuosity and inwardness, Sivanandan Master never tried to outshine Panjara on the concert stage; instead, he empowered Panjara to delve deep into the ocean of music.

Sivanandan Master did yet another great service by notating (saregama notation) about fifty of Panjara’s compositions. The original plan was to prepare notations of all the compositions. We intend to post the available notations on this site. Future students and performers can refer them to design their own performances.

In order to assess the life and contributions of Panjara, a comparison with his life and that of a legendary Keralite, Shri K. J. Yesudas, the playback singer and concert artist may be useful. This comparison is far from judgmental. Those who are familiar with the contemporary culture of Kerala might think that this is like comparing a goat with an elephant. In fact, that is what it is. Yet, there is something to learn from their personal histories. Both Panjara and Yesudas were born and raised in traditional Catholic families in Kerala. Early on, they were initiated into the Catholic faith, doctrine, and religious practices. During teenage years, they received training in South Indian, Karnatic classical music. They both learned the usual repertoire that are mostly in praise of Hindu gods and goddesses. Their teachers were Hindus. The similarities of circumstances end there. After completing the music education, Yesudas started playback singing for Malayalam films. Because of his exceptional talents and his self-discipline to nurture those innate talents, Yesudas was catapulted into fame and became a great celebrity. Meanwhile, Yesudas also started giving concerts of Karnatic classical music. Because of the quality of his voice and knowledge of music, Yesudas became a living legend. In classical concerts Yesudas relied mostly on traditional repertoire of Hindu devotional compositions by venerable composers in South India. Not only that, Yesudas went one step further by developing an affinity toward Hindu religion enough to adapt some of the religious practices into his personal life.

Panjara, on the other hand, took an entirely different route after completing his music studies. He used his training and knowledge in Karnatic music as a booster rocket to enter into another space that he defined for himself. Instead of singing the traditional repertoire of classical compositions with Hindu themes, Panjara turned to his Christian faith that he inherited. However, there was a major hurdle. There weren’t enough classical compositions in Malayalam for a concert artiste to rely up on. So, Panjara decided to create compositions in the Malayalam language. As we saw earlier, he used biblical lore as his source of inspiration. That determination became a great boon to the classical music repertory in Malayalam. A new branch of music was born. On the concert stage, Panjara sang his heart out with an elegant diction and a broad smile. He sang to the Lord and the Blessed Virgin Mary with pride, without shame. The song text emerged out of his personal devotion and deep rooted faith. Similar to the Christian devotional poetry of Kochukunjupadeshi 1883-1945, the words carried a personal intimacy that flowed into the melodies and their vocalization.

In comparison, both Yesudas and Panjara had similar trajectories in their formative years, yet emerged differently in the later years. In the process, Panjara left us a unique legacy that no other Keralite could; he added a corpus of Christian compositions in the Karnatic classical style, thereby enriching the cultural heritage of Kerala. It is up to the forthcoming generations to enjoy and build up on the foundation that Panjara laid.

A comprehensive assessment of Panjara’s contributions is incomplete without a musical analysis of his compositions. Such a venture is beyond my capability. The Christian Musicological Society is open to any contributions of that nature by Karnatic music connoisseurs. We shall gladly add those contributions to this web site.

Tribute to Sri. George Panjara

Funeral Speech by Dr. Joseph J. Palackal , C.M.I.

Vidwan George Panajara Anusmarana Sangtheetharchana A Musical Tribute to Late George Panjara on 21-July-2018 organised by Chavara Cultural Center Kochi, CMSI and Nadopasana Thodupuzha at St.Xavier's Parish Hall, Kodavara, Vaikom, Kerala

| # | Description | Pdf Download | |

| 1. |

Shri George Panjara wins first prize in a music competition. 2004. (Published in Kudumbadeepam, February, 2005.)  |

||

| 2 | Letterhead and handwriting of Shri George Panjara.( Letter to Fr. Joseph J. Palackal on 17- June-2003) |

|

|

| 3 | Report on Shri George Panjara's concert at Cochin Arts and Communications Center, Ernakulam, organized by Fr. William Nellikkal, on Sunday, September 15, 2002. (Published in Kudumbadeepam. October 2002)  |

||

| 4. | First All Kerala competition for Christian classical music organised by CMSIndia and KCBC Media Commission held on 3-Sept-2001 at POC Hall, Ernakulam.

|

||

| 5. | Nadopasana (Society for the promotion of Classical and Choral Music) - Christian Classical Music Concert (Carnatic) - By Shri George Panjara at 5:30pm on 20-April-1986 at Upasana Auditorium , Thodupuzha . Fr. Joseph Palackal, CMI introducing the artists (Shri George Panjara in the center) before the concert.

Christian Classical Music Concert (Karnatic)Participants

|

||

| 6. |

|

ഞാങ്ങണയുടെ പാട്ട്Song of the reed Collection of George Panjara's poems, Published in 2002 The collection is an excellent tribute to Panjara’s exceptional poetic skills. Fr. Thachil’s stylistic Malayalam text defies easy translation; therefore, a scanned copy of the original pages are attached here for the benefit of curious readers |

|

| 7. | അയൽക്കാരൻ(The Neigbhour) Poem written by George Panaja, published in Kusumom ( Kerala's first Christian Family Magazine) |

||

| 8. | അഭയം(Refuge) A short story written by Geourge Panaja, published in Kudumbadeepam Magazine |

||

Photo Gallery - Program Appearences

Awards, Certificates and Recognitions

George Panjara’s mission to elevate the status of Christian music in Malayalam met with apathy and indifference from the general public, and the Catholics in Kerala. Considering both the quality and quantity of the compositions, Panjara’s name should have enjoyed the same recognition as that of the Karnatic classical trio Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dhikshitar, and SyamaSastri music lovers in South India. However, his greatness as a divine minstrel, his unique talent as a composer, and the deep dedication to his faith give George Panjara a prominent place in the history of Christian music in India as well as Karnatic music in Kerala. Through his determination to perform his own works, Panjara paved the way for a new stream from the great ocean of Karnatic music.

Panjara’s legacy is more in the area of composition than in performance. Expert performers can make use of the large body of resources that he has left behind in the form of audio recordings and music notations. There is no doubt that the Panjara legacy is large enough to give him a page in history books on Kerala culture as well as Karnatic music.George Panjara’s life and works deserve a much more in-depth study. His life is also a social commentary on the cultural sensitivity of the Christian community in Kerala. Future scholars may place Panjara in the league of the poet-composers in the Hindu Bhakti tradition in South India. These poet-composers were intoxicated with devotion; poetry and music overflowed from their faith-filled hearts. They were in a daze, often oblivious to the mundane aspects of everyday life. Indeed, for Panjara, music was not a profession, but a calling. He used his breath ( šwāsam in Malayalam) to enliven his faith ( Interestingly, the Syriac word haymānūsā, and the English word “faith” are rendered in Malayalam as wišwāsam, which literally means “special breath.”). Panjara did not think of himself as a composer or performer, but as a vehicle of God experience. To George Panjara, there was a sense of mission; monetary benefits were not his concern

Such multitalented individuals as George Panjara, who are equally proficient in poetry, music, performance, and deep commitment to Christian faith, are a rare happening. Sometimes, the world may have to wait even a century to discover him, as it happened to Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), the godfather of Western art music. J. S. Bach had to wait for almost a hundred years in the silence of an unmarked grave in Leipzig for Felix Mendelssohn to remove the lid of obscurity and make his massive choral master pieces alive to the musical world. Meanwhile, Panjara is adding yet another dimension to the soundscape in heaven, and also a new musical style in Malayalam. We can be sure that Jesus will place him on his right side with the words: “Come, George, who is blessed by my Father, inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.”

Let the music go on. And it will. Because, unlike performers, composers do not die; they relive through every performance of their compositions by generations of performers across time and place.